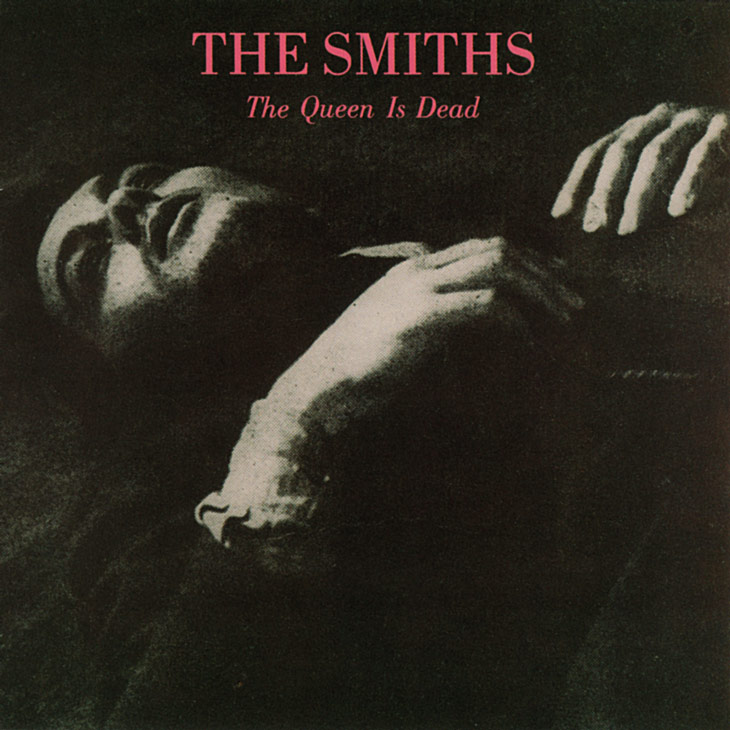

The Smiths - The Queen is Dead

“Has the world changed or have I changed?”

Right answers are self-perpetuating: you start with one, then you notice a counterargument; you try to correct the contradiction, and another is born; soon you’re addressing them one after another, until you’ve arrived where you began. The Queen is Dead – and the Smiths – embody this paradox; and I mean that in the best possible way…mostly.

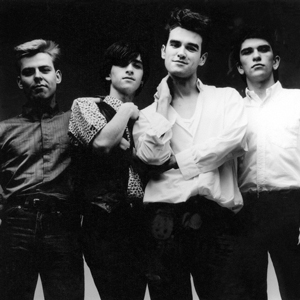

If you were to judge The Smiths by this record, you could almost argue that they were pop-music by numbers. Just listen to Johnny Marr’s distinctive, resonant, arpeggiated guitar lines that suggest chords, and progressions more than play them; listen to the sultry tenor of Morrissey, slithering across the songs melodious and full, songs that almost demand you sing along to them; listen to Andy Rourke and Mike Joyce holding the line with indistinguishable bass and drums. The progressions are minor chords that harmonize like majors; the sound is full but exists in the spaces.

And then Morrissey’s lyrics show up, and you realize this isn’t pop-music. Morrissey’s cynicism and unwavering irony – his love of caustic attitudes and Cilla Black – bleed dry that notion. The fascination with empty fame, death, lust, the need to exist: that’s pure underground. This is an angry album, propped up like a love song.

It is also, uncoincidentally, among the definitive underground releases from the ‘80s, a decade which gave the underground a voice, reason and artistry. It’s a mixture of punk and crooner, and made the jangly beauty of a Rickenbacker property of the independent, where once it stood tall as the sound of pop music by the Beatles, the Hollies, and the Byrds. It gave underground and indie commercial viability, critical notice and regard. It was part of a large scale pivot in commercial interests that would ultimately usher in bands like Nirvana and Arcade Fire. And, perhaps ironically, it began the shift of underground to pop, and not just in the musical sense.

The fascination with empty fame, death, lust, the need to exist: that’s pure underground.

In that circular logic, I find my enjoyment of this record, within Marr’s compelling spacious melodies, Morrissey’s lush vocals and ironic lyrics. It has the visceral satisfaction that great commercial pop brings, with the heady realism that only underground has the space to express. The lyrics – so often morbid and cynical – make me laugh in recognition. I see outsiders having fun with those on the inside, and making it their own, using pop to be its anti-pop.

It is in that same circular logic, however, that I frustrate myself with this record. I find Morrissey to be an extreme personality; extremes frustrate me, and as a result, I find the lyrics often take it a step too far. Morrissey can be exceedingly cruel – even if accurate – in his assessment of people; and as someone who tries to sprinkle his pessimism with some positivity that is a thorough pain in the ass.

But damn, if it ain’t catchy.

Until the 21st century stops breathing down my neck