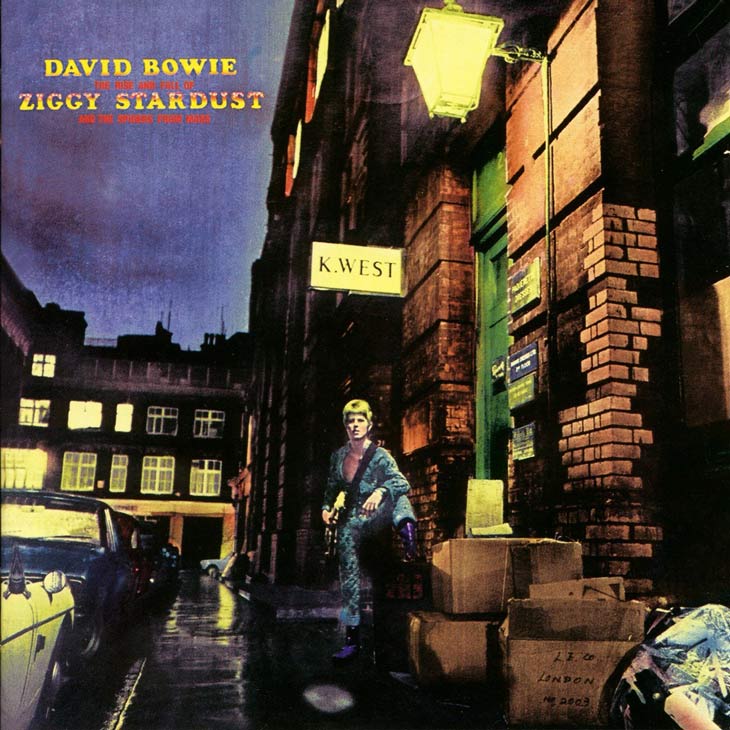

The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, and the Spiders from Mars.

Life is a sine wave, with peaks and valleys, and ups and downs. Sometimes you don’t know which is which, until time passes and hindsight comes. Sometimes music can stand on its own merits; but sometimes, one moment can define a record and opinions, more than any one thing. Such is my experience with Ziggy Stardust, and David Bowie.

David Bowie was a modernist in the vein of James Joyce. He loved to challenge form, and used a variety of them to serve one function—making you aware of the art in artifice, and vice-versa. Sometimes jazz, vaudeville, or cabaret would suit his purposes, and at other times, riffing on the Beach Boys or Lou Reed would. Ziggy is the most balanced effort in this vein: a groove-laden slice of hard-rock married to that modernist sensibility and a concept that is at once self-referential—an alien rock-n-roll savior, destroyed by the excess of stardom. This is the pinnacle of his achievements in my book.

I could go on, and give Bowie the eulogy he’s earned, and why this album is so good, but my opinion is influenced by something far more powerful, and personal: a moment in time when I was lonely.

I’m 16; the year is 2007; it’s mid-winter in suburban nowhere, and I’m on my evening walk, musing about a girl who was, at that point, Beatrice (there have been a number of them). The grass is sickly green and deadened by winter’s kiss, when I put on “Five Years,” the album’s opening track. Bowie mourns of the impending apocalypse, and I walk, wrapped in my thick beat up L.L. Bean jacket with my iPod for a companion. The sky, once blue, turns gray.

I could go on, and give Bowie the eulogy he’s earned, and why this album is so good, but my opinion is influenced by something far more powerful, and personal: a moment in time when I was lonely.

“Soul Love,” a gentle ballad, follows —the birth of Ziggy—and a thick fog descends. I walk through it, my earphones closing me off from other sound. As the music transitions to “Moonage Daydream,” It starts to snow, making a silent storm. The suburbs around me disappear in the swirling white haze. A child hears Ziggy Stardust message of rock n’ roll saving humanity in “Starman,” and I imagine him in his bedroom, longing to escape the suburbs for outer space. The Beatrice of sophomore year tortures my heart as “It Ain’t Easy” and its creaking stairway piano riff comes on.

The first phase of the walk ends as the trans-ballad “Lady Stardust” comes on and act two begins. The storm slips me into a silent cocoon of white, and I think about myself and my tendency to enjoy being weird. “Star” begins and the wind picks up; I linger on Beatrice to shameful excess, and my own sense of utter powerlessness pulls me forward. Muscle-memory takes me towards the strip mall that marks this walk as the forward thrusting “Hang Onto Yourself” cranks up the glam guitar. I make my way, progressively across sidewalk, parking lot, and dimmed light in the silent, swirling white apocalypse.

Those monstrous chords or “Ziggy Stardust,” his doom writ large in Bowie’s lament to excess and ego enter with the final phase of my walk, and the storm peaks in transcendent glory. I’m in the wood behind the strip mall, where trees stand sentinel over peaceful mundanity. I’m headed to what I call my happy place, to calm myself. The snow, despite its ferocity, feels soft. The wind intensifies and the fog climaxes to Bowie’s ode to the Beach Boys, “Suffragette City.”

Then, suddenly, it stops. Wham, Bam, Thank you ma’am.

Almost as abruptly as it comes, it goes—worn out, alone, and dead. The gentle, tired, poorly compressed, refrains of “Rock ‘n’ Roll Suicide” enter, as I do, to my little Shangri-La: a large field, ringed by trees, where I’m free to be me. Reaching my happy place, the storm stops and Bowie screams “Oh No Love You’re Not Alone,” while the song’s orchestral climax syncs perfectly to the moment I step onto the chilled wet grass. The sky clears into a purple, pink kaleidoscopic wonder. Then the album ends. I feel emptied of myself; and, I don’t feel alone.

I may not love this album, had I not had such a powerful moment accompany it. But this album came in a storm, and told me I wasn’t alone, making the music far more meaningful than any analysis could render.

Life is a sine wave, and sometimes, we’re rising when we think we’re falling; good thing for me, Bowie was there to show me the way.

Until I’m a Rock-n-Roll Suicide.