You could call them the Vincent Van Gogh of emo music, if Van Gogh had the ability to resurrect himself from the grave after finally receiving recognition.

It’s late ‘90s in Champaign, Illinois—a Midwestern college town that offers a tiny haven from the endless sea of cornfields and soy factories. American Football is mostly a group of college kids jamming together. As guitarist and lead singer Mike Kinsella tells Pitchfork, “When we started making music, it wasn’t to be popular, or even be a band.” They record some tracks in the vein of post-hardcore and emo, play a couple garage shows, and break up.

Fast forward a few years, and something weird happens. Suddenly the underground music scene is buzzing about their self-titled 1999 release. Why?

American Football’s popularity coincided with a slow rise of “emo” music among underground listeners, right before it exploded in the mid 2000s, when MySpace and Hot Topic helped unleash a frenzy of skinny-jeans-wearing, raccoon-eyelinered adolescents with hair dyed every color of the Manic Panic rainbow.

The term emo actually emerged from the ‘80s hardcore punk scene, with bands like Rites of Spring and Embrace (fronted by Minor Threat’s Ian MacKaye) seeking to broaden the genre’s creative scope both musically (bringing more melodic tunes to the traditionally noise-driven genre) and lyrically (focusing more on individual experience, emotional release, and deep personal confessions). In the early ‘90s, Sunny Day Real Estate and Jawbreaker kept the genre alive. These originals sound worlds apart from the Warped Tour acts that popularized emo.

American Football bridges that gap, both chronologically and stylistically. Their shimmering soft guitar melodies pull the genre even further from its hardcore punk roots, and their nostalgic suburban longing and almost nasally vocals are a precursor to bands like Taking Back Sunday, New Found Glory, and Something Corporate.

According to Kinsella, their album became “a rite of passage for young kids getting into emo music, for whatever reason.” Fans who looked backward found their curiosity rewarded with overlapping guitars, varying time signatures, jazz influences, lengthy post-rock like overtures, and poignant horn solos.

The magic of their first self-titled was in capturing a zeitgeist for a group of teens in the early 2000s.

But they would never see American Football live or hear a new release. Until now.

In 2014, American Football surprised its faithful herd of underground followers by getting back together for a 15-year reunion tour. Now, they’re releasing a new album on October 21 before setting off to perform it live in a handful of cities.

But what emotions will they relate now, 17 year later, and will they still capture us?

The magic of their first self-titled was in capturing a zeitgeist for a group of teens in the early 2000s. It reeks of melancholy teenagehood—wondering how to say goodbye at the end of summer (“…with a handshake? Or an embrace? Or a kiss on the cheek?”) and melodramatic breakups (“You can’t miss what you forget, so let’s just pretend…anything between you and me was never meant”).

It’s relatable now, but nostalgically—there’s a longing for problems so simple after 10 years of adulting.

Herein lies the dilemma. American Football’s fans are now adults with careers, spouses, and children. As are the group’s members, who talk about consulting their wives and families before making the decision to reunite.

The debut track off their new album, “I’ve Been Lost So for So Long,” is promising. It keeps their plain-spoken, confessional style but thematically, it’s years apart (17, to be exact). It hinges on disappointment (“If you find me, could you please remind me why I woke up today”) and disillusionment (“maybe I’m asleep and this is all a dream”). It even brings up the common adult-to-adolescent refrain— “it doesn’t get easier”—as if warning the kid-selves who wrote their first album.

There’s a profound loneliness and confusion that convey the difference between sadness then and now. Rather than talking directly to friends and lovers, emotions are mostly directed at a vast, empty abyss, or at imaginary figures—“doctor, it hurts when I exist.”

Many lyrics sound clichéd, but the band maintained the core ethos that powered the initiation of emo in the first place—honesty and openness. As Kinsella tells Pitchfork, “It’s not a lyric I’m sorta proud of, but OK, I actually mean it. It’s sort of embarrassing for me! It’s diary stuff.” It’s a sincerity we often don’t allow ourselves as adults, but maybe we should.

If going back to the first album feels like re-reading old diary entries, the new tracks off their second album feel like cracking those old diaries to write brand new entries. You find that your typical “growing up” themes—love, loss, learning—are just as present in adulthood, because we don’t actually “grow up”.

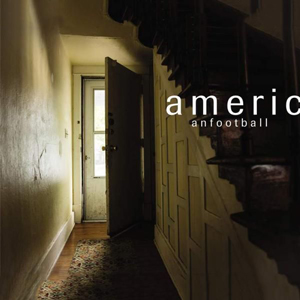

Cover photo by Brandon English