I plugged 16 shells from a thirty-ought-six and a black crow snuck through

a hole in the sky, so I spent all my buttons on an old pack mule and I made me a ladder from a pawn shop marimba, and I leaned it up against a dandelion tree.

A blinding hangover makes for a bad introduction to Tom Waits, at least if it’s the album Bone Machine turned up to 11, as my roommate decided to do one Sunday morning in 1995. In the pain pulsating through my frontal lobes, the guttural roar of “Earth Died Screaming” sounded like a jagged, bloody set of nails being scraped across a chalkboard.

However, the white hot hatred of the moment burned equally strong with love not long after, as the independence of the Waits’ sound and vision overcame me (drunk or sober). Perhaps no greater example of this can be seen than in his 1985 album, Rain Dogs. While the Billboard charts saw Wham!’s “Careless Whisper,” Madonna’s “Like a Virgin,” and Foreigner’s “I Want to Know What Love Is” reach to the top, Waits put out growling back-alley dirges like “Singapore,” “Clap Hands,” and “Jockey Full of Bourbon.” And yet, whatever artifice was layered on top of the tracks, at the root were often the sweetest and purest of melodies seemingly pulled from generations of collective yearning.

Tom Waits’ lyrics offered as deep a pool of genius as his melodies—biting, funny, raw, and outright bizarre—as if the poetry of Charles Bukowski was dumped in a blender with broken whiskey bottles and used automobile parts. Through his songs, I learned such truths as “There ain't no devil, that’s just God when he's drunk,” “There's always free cheddar in the mousetrap,” and “You’re innocent when you dream.”

For those new to Waits, asking where to begin is akin to debating the best position for sex. Whichever you choose, it’s still fucking great. That said, these five albums form the main pillars of my undying devotion to the artist that is Tom Waits.

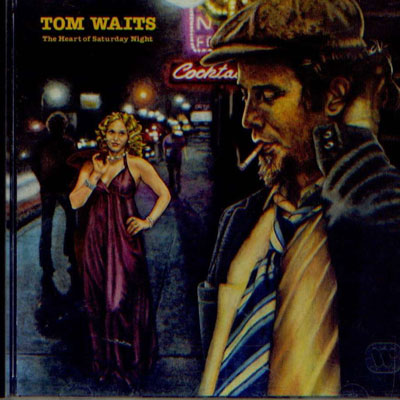

Heart of Saturday Night (released 1974)

Frank Sinatra looms large in this late-night, booze-soaked collection of ballads and jazz scats, the follow up to his debut album Closing Time. Indeed, the cover of Waits coolly smoking outside a late night bar is pulled directly from the cover of Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours, and topped up with garish neon signs and the salacious looks of a prostitute. “New Coat of Paint,” starts off the album with a call to arms, or at least cheap bourbon: Let's put a new coat of paint on this lonesome old town/ Set 'em up, we'll be knockin' em down.

The album goes forward full of Kerouac-inspired headiness, with spurts of bravado in songs like “Fumblin’ with the Blues” (Fallin’ in love is such a breeze) and “Depot, Depot,” (This peeping-Tom needs a peephole) alternating with depressive yearnings in “Shiver me Timbers,” “Please call me Baby,” and “Drunk on the Moon.” But it’s in the more sentimental moments, like “San Diego Serenade” and the titular “Heart of Saturday Night” that tears can flow, particularly if it’s late at night and you’re all alone.

Instrumentally, the tracks pay heavy tribute to ‘50s’ beatnik jazz and early ‘70s’ folk with swinging horns, hopping bass, weeping strings, and tinny piano—all of which could easily come from the back corner of a scuzzy bar on Tin Pan Alley. But instead, they come from a crack band of session kings like Jim Hughart, a veteran of Ella Fitzgerald’s touring band, on double bass; tenor saxophone Pete Christlieb, later of The Tonight Show band; and drummer Jim Gordon, who; after racking up credits with Derek and the Dominoes, Joe Cocker, and Traffic; murdered his mother in a fit of schizophrenic rage, earning him a long stint in prison, where he resides today.

Blue Valentine (released 1979)

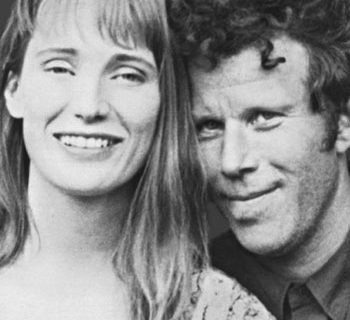

There’s a searching in the violin strains of “Somewhere,” the West Side Story ballad that starts off this album, which, in many ways, marks the end of the first era of Tom Waits. Indeed, it’s the last album recorded before Waits met and married his muse and future collaborator Kathleen Brennan, a partnership that would lead to the artistic breakout of Swordfish Trombones four years later.

Once more, a somber, downcast Waits graces the dimly lit scene of the cover, while the cheap neon and slinky seductress’ (then lover Rickie Lee Jones) get the backside. So too, do the same old characters of Waits’ earlier work populate the 10 tracks: the small-time gangster, the tough whore, the barfly, the freight train, the night clerk with a club foot, and bleeding Romeo—all introduced with a hiss and a slither both sad and sexy.

But there’s clearly been significant development of Waits’ talents, particularly in the lyrics department. The stunning word imagery, even when making little sense (like much like Bob Dylan’s), becomes instantly gripping, if only for the crash of consonants and vowels that throw sparks like tinder scraping iron pyrite. Just try to say, The cold jingle of taps in a puddle was the burglar alarm snitchin’ on Caesar in “Red Shoes by the Drugstore,” or, The wolfsbane blooming by the trestle in “Wrong Side of the Road.” The linguistic friction adds a tremendous sense of energy and swagger, even when the content doesn’t justify it. But it’s the album’s sublime moments of raw truth that penetrate to core. When I get a little bit lonesome and a tear falls from my cheek / there's gonna be an ocean in the middle of the week Waits raps in “Whistlin' Past the Graveyard,” while in “Blue Valentines,” he croons, The ghost of your memory/Baby it’s the thistle in the kiss."

And then there’s the absolute gem, “Christmas Card from a Hooker in Minneapolis,” perhaps the best song Waits had written to date. In it, we watch the rise and fall of a dream in few simple stanzas couched in mirroring up-and-down arpeggios on the piano, transforming a loving husband and pregnant belly into prison bars and debt.

Charlie I think I'm happy for the first time since my accident

And I wish I had all the money we used to spend on dope

I'd buy me a used car lot and I wouldn't sell any of ‘em

I'd just drive a different car every day depending on how I feel

If the man only wrote this one song, it alone would be a worthy life’s achievement.

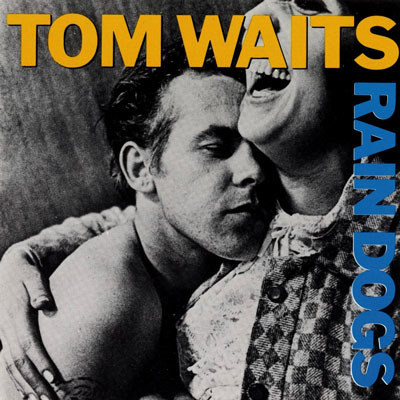

Rain Dogs (released 1985)

Swordfish Trombones may have blown down the walls of Waits’ musical vision and voice until then, but the move reached full maturity in the follow up Rain Dogs, lauded by many as the greatest work of his career. Certainly, it’s a wild ride through the 19 tracks that sound like a Weimar Republic cabaret MC’d by William S. Burroughs, starting with album opener “Singapore,” which proudly proclaims, We're all as mad as hatters here. Follow up “Clap Hands” sounds like it’s played on xylophone made of bones, while a church bell intones ominously in the distance. The track also gives guitarist Marc Ribot, whom Waits instructed to play like at a “midget's bar mitzvah,” his first chance to shine and so he does throughout the album, contributing significantly to the sound.

He’s by no means alone either in his stellar contributions, joining at least 20 others, including Keith Richards; who takes over guitar duties on "Big Black Mariah," "Union Square," and "Blind Love;” bassist Larry Taylor of Canned Heat fame; saxophonist John Lurie from the Lounge Lizards; and Michael Blair on percussion, marimba, congas and the bowed saw. Waits himself adds the harmonium, pump organ, and banjo to his usual oeuvre of guitar and piano.

The lyrics match the insanity, play, and genius, from Uncle Vernon/ Independent as a hog on ice, in “Cemetery Polka” to Bloody fingers on a purple knife/ A flamingo drinking from a cocktail glass in “Jockey Full of Bourbon” to They take apart their nightmares/And they leave them by the door” in “Tango till they're sore,” or this exquisite stanza in “Time:”

When she's on a roll she pulls a razor

From her boot and a thousand

Pigeons fall around her feet

Strangely, towards the end of the album, the pop clouds seem to part for “Downtown Train,” a track that shot to number one on the billboard charts four years later under the sugar-coated auspices of Rod Stewart. The title also pays tribute to the New York City influence that runs through much of Rain Dogs, including tracks like “Union Square,” “Midtown,” “9th and Hennepin.” Considering, most of the songs were written in a basement room at the corner of Washington and Horatio Streets, it makes perfect sense.

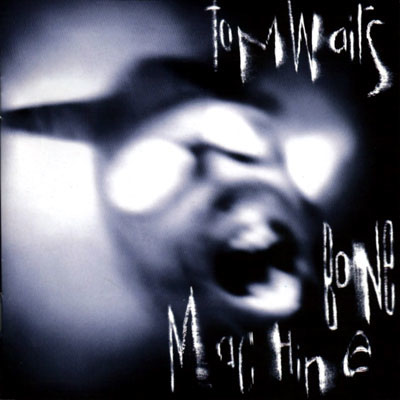

Bone Machine (released in 1992)

By 1992, Waits had achieved grand pooh-bah status and the respect and deference of nearly any serious songwriter. Had he put out nothing more ever again, he could still easily have rested easy on his laurels. Instead, Waits issued another assault on the senses that turned over the apple cart once again, starting with the dancing bones and guttural roar of “Earth Died Screaming” and the lyrics like Hell doesn't want you/And heaven is full/Bring me some water/Put it in this skull.

Indeed, death and damnation rule the album, from the blurred cover photo of Waits in a leather skullcap with horns and protective goggles to tracks like “Dirt in the Ground,” (We're all gonna be just dirt in the ground), “Jesus Gonna Be Here” (Hollywood be thy name), Black Wings (He once killed a man with a guitar string), and Murder in the Red Barn (There’s always some killin’ you got to do around the farm). With such a future, it’s no wonder the great sing-along track of the album screams, I don’t want to grow up.

The instruments—a mash-up of Waits’ usual oeuvre of piano, guitar, accordion, banjo, saxophone, and violin, and sticks—are played by old friends Keith Richards, Larry Taylor, and Ralph Carney, and new ones Les Claypool, Brain, and David Hidalgo. In the track “In the Colosseum,” the industrial crashing comes courtesy a newly invented percussion instrument built by Waits’ neighbor: the Conundrum, which Waits describes “kind of like a Chinese torture device," with a lot of metal hanging off an iron cross.

Bone Machine is not the easiest album to fall for on the first listen, but when you do eventually, it’s until death do you part.

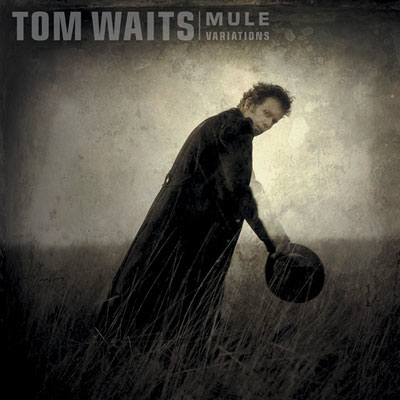

Mule Variations (released in 1999)

While the world panicked over Y2K, Waits released one of his most commercially approachable albums of his career, or so it seemed following Bone Machine and the subsequent William S. Burroughs collaboration of The Black Rider. It’s not immediately obvious, however, until you get past the industrial crunch of opening track of Big in Japan, but by track 3, “Hold On,” you’ve entered Grammy territory (nominated for Best Male Rock Performance), with one of the sweetest melodies and vocals Waits has ever produced softly dropped on a relatively straightforward country blues arrangement of guitar, organ, bass, and brushed drums.

The rustic sound—often spiced with the blues harp of Charlie Musselwhite or John Hammond Jr.— continues throughout much of the album in tracks like “Get Behind the Mule (inspired by blues legend Robert Johnson's father, who complained his son wouldn't “get behind the mule in the morning and plough."), “House Where Nobody Lives,” “Pony,” “Picture in a Frame,” and “Come on up to the house.” Much of this ambiance can be attributed to the location of the album’s recording, a converted chicken coop in northern California.

Lyrically, Waits is also more straightforward than usual, but no less compelling and powerful, particularly in the sentimentality in tracks like “House Where Nobody Lives, which declares, “What makes a house grand/Ain't the roof or the doors/If there's love in a house/It's a palace for sure. In “Picture in a Frame,” we hear Sun come up it was blue and gold/ ever since I put your picture in a frame. That’s not to say there’s not plenty of the usual oddities, with the “Eyeball Kid” (born without a body), “Filipino Box Spring Hog” (Kehoe spiked the nog/ With a chain link fence/ And a scrap iron jaw) but perhaps none scratch as much heads as the spoken word performance “What’s He Building in There,” which monologues on one neighbors paranoia and suspicion for another: He has no friends/But he gets a lot of mail/I'll bet he spent a little time in jail.

The curiosity is not dissimilar to the reason fans continue to parse and grasp some tiny morsel of Waits’ genius, which is so unlike any other. Although it remains a mystery, (even after dozens of appearances on Letterman and YouTube videos), all we really care about is that he keeps building something in there.

Cover photo by Nicola Boccaccini, used with permission.