Above all things, I desire harmony.

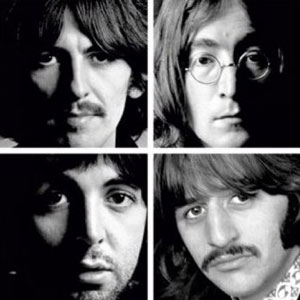

For me, the Beatles were at their best when they functioned harmonically as a group: each member’s strengths and weaknesses played off of each other, creating a sense of balance and function. Where John was all chords, Paul was all melody; where George was lyrical and sorrowful, Ringo was straightforward and upbeat. That chemistry—at its best—was alchemical, and created the gold that made the Beatles, the Beatles. Their self-titled album, released in 1968, ironically, marks the moment where they stopped being a group.

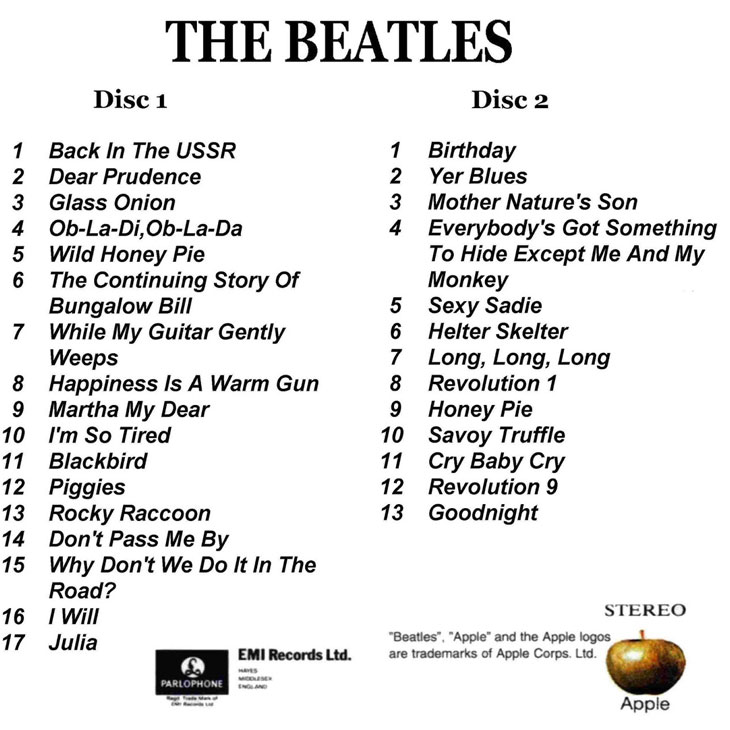

The Beatles White Album

The White Album is four solo records, if we’re being honest. Lennon is acerbic, caustic, aggressive and experimental in his contributions (Glass Onion, Happiness is a Warm Gun, Revolution 9); McCartney is so gentle, it feels like a reaction (Martha My Dear, Honey Pie, Blackbird); Harrison is finally earning the light he so richly deserves with his melodic sorrow (While My Guitar Gently Weeps), and hey, look, Ringo wrote a song too (Don’t Pass Me By). That joke is too easy to pass up, sorry Mr. Starr.

One many tracks, the contributions of the other three is perfunctory at best, and non-existent at worse. You can hear where Ringo isn’t present on the song, “Back in the U.S.S.R.” as McCartney plays a straightforward no nonsense drumbeat that lacks all the character of Ringo’s singular style. When the band isn’t angry at itself, it’s angry at its listeners; “Glass Onion” is John Lennon’s boiled over frustration is so extreme he makes fun of fans for over-reading his work. The song “Revolution 9”, while a wonderful piece of experimental music—yes, I just said that—is so fundamentally despairing and psychotic, that pairing it against the most overtly gentle and sweet “Good Night” feels like a sucker-punch.

That chemistry—at its best—was alchemical, and created the gold that made the Beatles, the Beatles.

And in many ways, that sense of anger, and imbalance on a band level, is why this album ultimately ends up being one of the Beatles strongest albums. Instead of Lennon’s chords against McCartney’s melodies, it’s anger versus sweetness. The songs are so radically of the self, that the tension of their difference sustains the 30 tracks. Add to that the overwhelming musical confidence and competence of the Beatles, and that harmony is achieved.

In the absence of people, music has been my tension. When I listen to music, I find a peace in being myself. In many ways, music is almost a physical person for me. And this album, like the entire catalogue of The Beatles, was a harmonic tension for my life. I’ve listened to this album so many times, I can’t pinpoint a single crystallized memory—in Boston Common on sunny carefree days, in my dark winter of my teenager years, in mountains of snow, at the heights of ecstasy. Finding and losing passion. It’s been there throughout all of it. It’s one of my favorite albums. But it hurts to know that Harmony was achieved through such pain.

But, as in all things, Harmony is not often accomplished easily. And I desire Harmony, above all.

Until Number 9, Number 9, Number 9.