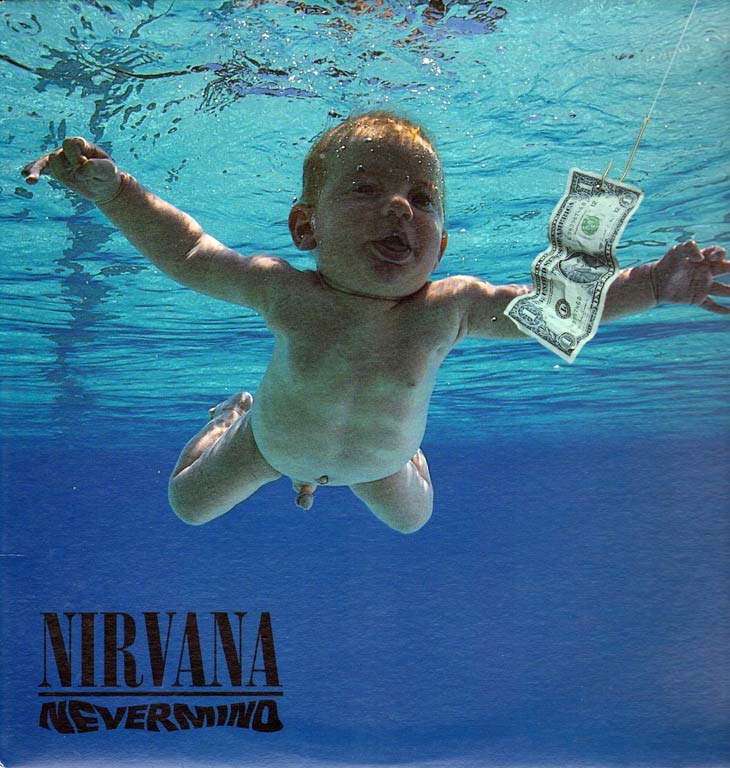

Nirvana Nevermind

I recently re-read Catcher in the Rye, by J.D. Salinger, and lamented Holden Caulfield; he is alienated by his own hand and querulous, unstable, and caustic. He is also damnably perceptive and powerfully relatable, even if, at the end of the day, that’s not a good thing.

Nevermind’s appeal is not just in the potent, melodically driven, punk-pop-metal fusion that became grunge and defined the early 1990s. It lies just as largely in the persona of the man who killed the king of pop to hail the apathetic proletariat; the herald of Generation X’s ascent into the mainstream; a man whose sense of self was so strong that he made the sounds of metal pop-staples: Kurt Cobain.

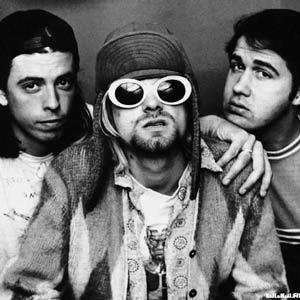

The cult of Cobain is as essential to understanding this album’s acclaim as the music itself, which is tightly played and beautifully produced by a balanced musical unit. While Krist Novoselic’s crunchy melodic bass; Dave Grohl’s loose, yet lock-step drums; and Butch Vig’s spit-shine production are vital, it is the character that Cobain creates on the album—an angry, alienated loner who doesn’t care if you like him—that sparks the power.

I loved—and love—Kurt Cobain, and his persona: He’s purposely angry, sarcastic and self-effacing. On this album, he makes fun of his own fans (In Bloom), celebrates bipolar disorder (Lithium), sings about his own incompetence (Smells Like Teen Spirit), and freely steals The Pixies quiet-verse/loud-chorus dynamic. Even when he cuts others down, he cuts himself down: he’s an egalitarian cynic. Yet, a man who can’t even feign love for himself was nevertheless loved.

it is the character that Cobain creates on the album—an angry, alienated loner who doesn’t care if you like him—that sparks the power.

Coming as you are—making yourself vulnerable on purpose—is terrifying. When that vulnerability includes self-hatred, unattractiveness, an inborn knowledge of being different and not living up to social standards, the terror is paralytic. Seeing somebody embrace that vulnerability with such integrity, such passion and honesty may not be the sole reason Nevermind made such a lasting impact, but it is certainly an important one.

In my teens, the same feelings often alienated me from those who I cared about. It made me a weirdo, a freak, a loner. I would go home and enjoy the hell out of this album about a million times, because I found a resonant note in Cobain’s own pain and self-deprecation. I still love this album, it has been with me through much. However, I don’t listen to it nearly as much these days, as it doesn’t serve the purpose it used to. But I still shamelessly play air guitar, sing, and dance as my prerogative. I am shameless about it and happy, and these days, it’s more a benefit than detriment. I am myself, and I have a voice, and I am proud of it.

When I do listen to this album now — like reading Catcher in the Rye — I’m struck by how tragic it sounds, and not for the obvious tragedy of Cobain himself. Although I thought it was great when I was young, to see someone openly cynical and pained, I’ve found that I’m too loving to feel comfortable with that identification anymore. Rather, I identify with those aspects of Cobain that are admirable, just like with Holden: honesty, integrity, and perceptiveness, even if that expression is layered in self-hatred, cynicism, and pain. At the end of the day, it is those former qualities that make the latter so powerful, and, ultimately, what give this album such a transcendent quality that it is considered the third greatest album of all time.

Until I come as I am.