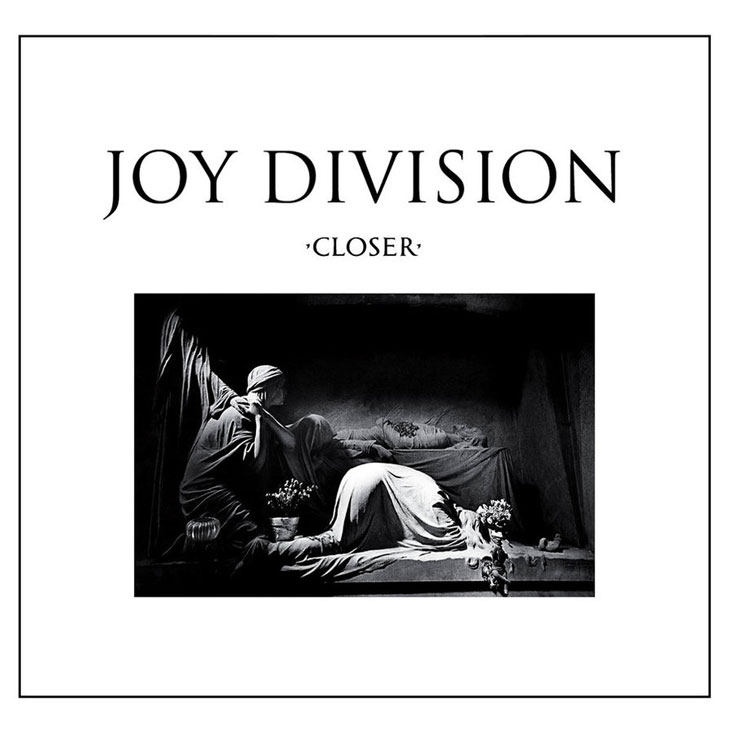

Joy Division - Closer

“I’m ashamed of the person I am”

I spent 24 of my 26 years steeped in abiding self-hatred; self-hatred–despite how it sounds–is a passive disquiet and a shroud over the soul that beggars transparency. It is a viscous ooze that drips over action and justice. It makes unfairness OK; it makes life look like a gaping maw. It makes worthlessness truth. It is an abyss. It is something Ian Curtis knew too well, and it hangs above Joy Division’s final album, Closer, released in 1980, like a sword of Damocles, poised to destroy everything.

If silence has a yin and yang, this album is most definitely a yang. The silence is wide and black, and the songwriting serves despair. The instruments reflect this, too: straight bass runs, repetitive drums, anorexic guitar lines, and epileptic keyboards, as if pulled from the rape rooms of Nazi concentration camps that gave the band its name.

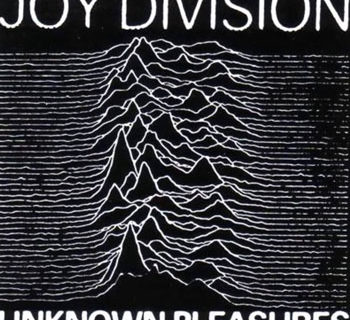

I can’t listen to this album without hearing Curtis’s death, which followed shortly. While the band’s debut album, Unknown Pleasure, is a gaping and terrifying post-punk work, it has moments of sanity and space to breathe, enough to keep it from the depths. In Closer, however, each track is a small death. High energy tracks like “Isolation” jitter uncomfortably. Songs like “Atrocity Exhibition” meander down the same road, like someone caught in a loop. The context grabs too much to avoid. It feels final.

But it is the gaping, febrile, and gangrenous silence that terrifies and becomes more important than the sound.

I know every avenue of this album’s emotions. Those moments of abject personal despair are like windows to the past. I see those moments where I overthought myself into stupors—darkness with no end in sight. I see the sludge in myself. I thank every day I escaped it. Ian Curtis, just 23, did not and succumbed to the end of a rope.

I don’t like listening to this album. It awakens dark things in me that I laid to rest as I learned to love myself. But I can’t help but enjoy it when I do. This is an exquisite sorrow. It may be too abject for me, but it is so indelible in its misery and utterly distinct. It forecasts post-punk so broadly that I can’t help but to appreciate it.

I wonder how I would feel, if darkness wasn’t my friend.

Until the procession moves on, the shouting is over, praised to the glory of loved ones now gone