“Frank is such a strange creation that I hardly know how to describe it. Wordless, timeless, placeless, full of unprecedented characters and experiences, it exists on its own bizarre terms. It offers vivid tableaus of tenderness and bloodshed, cruelty and sacrifice, love and betrayal, terror and bliss; and it offers them like candies from another planet.” —Francis Ford Coppola

As probably the only cartoonist who’s had an introduction written by the esteemed director, Jim Woodring might receive a MacArthur “genius” grant if only there were a category for Hallucinogenic Cosmos Imagining.

Of his entirely peculiar body of work, the most seamless components are the graphic novels Weathercraft, The Congress of the Animals, and Fran. The latter two books are each other’s prequels and sequels, as the characters experience an infinite loop of domestic bliss and alienation, bland normality, and the disintegration of anything approaching coherent reality.

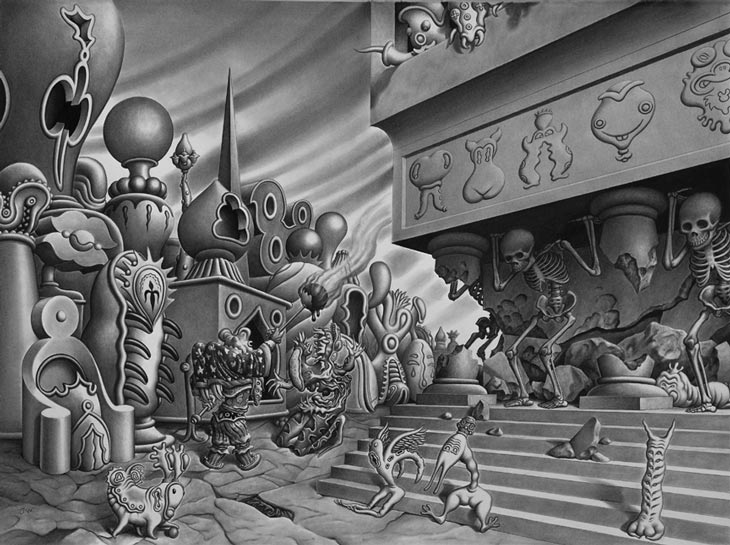

However, the mind-bending uniqueness of Woodring’s oeuvre should not obscure the elements of classical literature that lurk within. Look closely and you’ll see the Hero’s Journey, the skeletal underpinnings of almost every grand myth from The Odyssey to The Lord of the Rings. As the tales of a naïf wandering through a phantasmagorical landscape, the books channel a diverse array of works, from Dante’s Inferno and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. But just when you least expect it––that is, just when Woodring has begun to create narrative expectations––our protagonists are tossed in a disorienting direction, which may lead to the evaporation of their concepts of self (anatta, in Buddhist terminology).

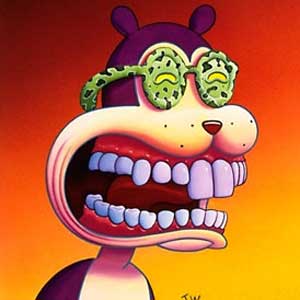

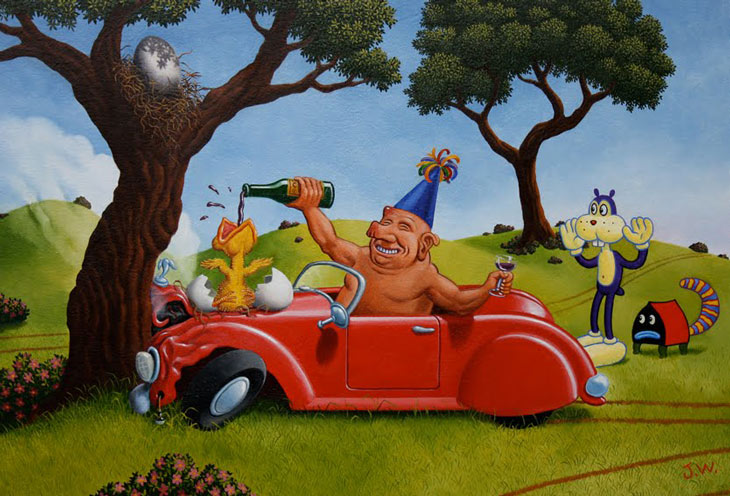

There’s Frank, a vaguely Disney-inflected, rodent-like creature. He is a wide-eyed innocent nonetheless capable of despicable acts without batting an eye. A perennial blank slate, he is the main perspective character.

There’s Manhog, who personifies every base desire and craven impulse, which makes it all the more disconcerting when he shows occasional glimpses of insight and civility.

There’s Whim, a lithe, cadaverous Lord of Darkness whose personal ad might read: “Wanted: Plaything of any species for experiments likely to result in your demise.”

And there’s Fran. I’ll avoid ruining surprises by saying only that she’s not who she appears to be.

So, why visit this land of ethically challenged miscreants? Because, like any significant work of art, Woodring’s world is a revealing mirror of the weirdness that we’ve come to accept as normal. In this case it is a funhouse mirror, but nonetheless the kind that causes an uneasy second glance over the shoulder as we momentarily recognize that yes, it is our own eyes looking back at us.

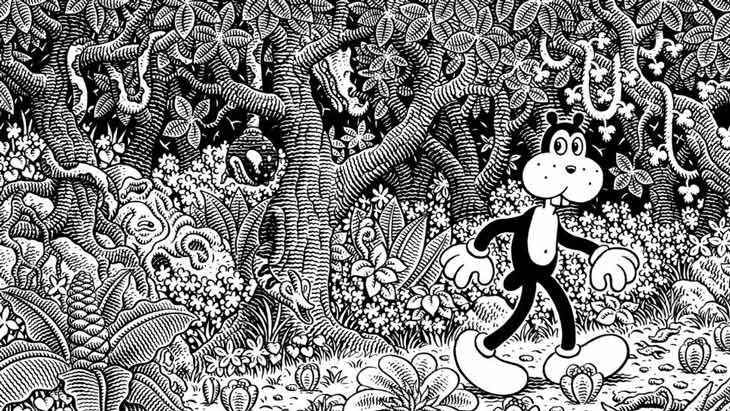

Woodring breaks the mold with his art, too. Scintillating, wavy parallel lines of varying thickness give the illusion of shading, even though his textures are all black and white (no halftone). Reminiscent of quill pen calligraphy or steel plate engravings, his imaginative backgrounds of lush gardens, claustrophobic interiors, and vaguely Islamic-inspired architecture appear to have been created the old-fashioned way, hand to paper. He expertly manipulates time via panel sequencing and maximizes drama with scale variation.

In the most compelling sequences, we float and emerge from one dream-like space to another, confronting bodies that melt, sprout extra features, and morph into bizarre hybrid species. We orbit a sphere of florid paisley shapes that blossom and engulf menacingly.

The Buddha instructed that eight worldly winds affect all lives sooner or later: pleasure and pain, praise and blame, fame and ill repute, gain and loss. This is the tune that we dance to, usually without even realizing we’re in the dance, and it was the Buddha’s perspective that waking up is liberation. Frank and his posse are even more clueless than the rest of us about the events that whipsaw them about, and under our voyeuristic gaze, they play out their assigned tragicomic roles with gusto.

Woodring invites us to grapple with the Big Stuff. In his cosmology our most basic assumptions about cause and effect are questionable. And yet, our primal desires for comfort and connection peer out of this vertiginous realm. The scope of his vision is startling despite, or perhaps because of, its concealment within the “triviality” of the comics medium. As Coppola concludes, Woodring’s work “is one man’s puzzling gift to a puzzling world… You may proceed with caution or not, as you like.”

If it takes madness to wake us up, then bring it on. The Woodring Asylum is open.

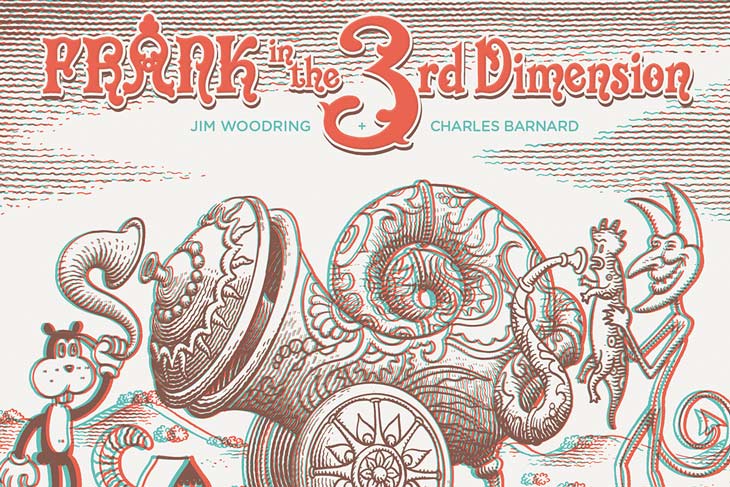

Your work is so spatially convincing and adventurous even in 2-D that 3-D must have felt like a natural fit.

JW: Yes, it sure did. In fact, I defy anyone to find any other cartoons that lend themselves better to 3-D than these. It's beyond serendipitous.

Did you find yourself modifying the storyline or drawing style now that you had access to 3-D?

JW: The images in the book were drawn long before there was even the glimmer of a notion that they might be converted into 3-D. They are drawings I made over the past ten years or so to work out scenes and situations for my comics. That they work so well for 3-D is a happy coincidence.

You’ve previously mentioned that you used to see “apparitions” that fueled your art, but that these have tapered off. Have you had any recent visitations, and if not, do you miss their creative force? Was the drawing of Frank in the Third Dimension graced by any inspirational hallucinations?

JW: I haven't had a bona fide hallucination in about three years. They didn't do me any particular good. They weren't inspiring or revelatory, other than being yet more evidence that we live in a flabbergasting situation.

Until I got used to it, I had a tough time reconciling your color work to your black-and-white. While the imagery is clearly the work of one artist, the Technicolor eye candy of the multicolored strips is so different from the old engraving look of black and white. I guess my reaction was, jeez, with this kind of linear skill, why does he need the bells and whistles of color? Do you have a preference for a certain look based on storyline, or does your choice depend on something else entirely (mood, lunar phase, etc.)?

JW: One of the compensations for the rigors of doing what I do is the ability to act on a whim, so if I think it would be fun to do a story in color I just do it without thinking about it very much. I slightly prefer working in pen and ink. It's an ongoing education.

Speaking of your black-and-white art, do you use any computer programs to achieve it? It looks totally handmade, but I’m in awe of the gradual line-width variation that you put in the wavy parallel lines, which allows you to achieve the look of shading and rounded contours. I can’t see how you’d be able to predict so accurately the overall tonal values while you’re doing it line-by-line. Did you ever study engraving or etching?

JW: No, I don't use the computer in the production of my comics at all. They are all drawn with a dip pen and India ink on Bristol. Working out the tones simply takes planning and the willingness to do it over if necessary. The book I'm working on now required redrawing six pages of a previous story line by line. It was excruciating work, but I had to do it to make a philosophical point. And no, I didn't study etching or engraving , I didn't go to art school at all.

There are few other quality wordless comics out there. Shaun Tan’s The Arrival immediately comes to mind. Funny, I always assumed that you didn’t use words because you were uncomfortable in that mode of expression, but then I see how eloquently you express yourself in interviews, and your explanation that you avoid dialogue because you want your work to be timeless and universal makes perfect sense. If I’m craving relief from language and all its potential distortions, can you recommend other comics artists that convey the whole shebang in image?

JW: There aren't that many that I'm aware of. Lynd Ward, of course.

So many teens feel alone and alienated, but if they’re lucky, they stumble upon their ‘tribe.’ I loved your story about going to the Surrealists exhibition and feeling, “My god, I do belong in this world after all!” I had a Salvador Dalí book in high school––remember the one that looked like a big, rococo, metallic candy box? I carried that thing around like a talisman looking for converts. With a distinctive body of work spanning decades, how do you feel your work has influenced the art and comics world?

JW: Undoubtedly Dalí affected me more strongly and for a longer time than any other artist. I wrote him letters, I dreamed about meeting him. In fact, I still have a recurring dream that I am hanging out with him and desperately scheming to get him to do a little drawing just for me. He never does.

Boris Artzybasheff and R. Crumb hit me almost as hard as Dalí. Artzybasheff's work always seemed freighted with inner meaning. That's what I wanted. As for my work's place in the field, who knows?

Now for the fan-nerd questions. The ‘kernel’ of Whim sometimes pops out and assumes the form of the hallucinogenic plant, Salvia divinorum. When he appears to be distorting the Unifactor (the alternate universe in which the action takes place), is that what’s actually happening, or is Whim just causing mind-melting hallucinations in the other characters?

JW: Whim is the wormlike creature. The devil-body is something he concocts out of biscuit. When he dives into the Salvia divinorum plant, he makes the plant his vehicle.

When Manhog has his transcendent experience in Weathercraft and stands on the threshold of Nirvana––I love how the entrance to “no-self” is a mirror without a reflection––he reluctantly turns back after seeing a compelling vision in the sky. He’s a grumpy bodhisattva, rather pissed at his new moral imperative to protect the defenseless. Many of us have performed compassionate acts with an element of resentment about the personal cost of not taking the easy way out. Was this a situation that you personally relate to or witnessed in your life?

JW: That episode is one of the few that has a pointed point that I grasp entirely. The same purity of spirit that brings him to the door of nirvikalpa samadhi obliges him to go and deal with the problem he has unleashed on the Unifactor. He becomes hyperaltruistic. He isn't exactly grumpy, but he's deadly serious. No, it doesn't correspond directly to anything in my life. Not intentionally anyway.

There’s a social network meme making the rounds. It’s George Orwell saying, “I told you so.” It appears that Whim is multiplying before our eyes like Mickey’s broom in The Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Your work has always included pointed sociopolitical commentary. The self-serving buffoonery we’ve got going on, now masquerading as responsible grownup behavior, seems like a mutant outgrowth of the Unifactor. Any thoughts on where this phenomenon might lead in your future work?

JW: Actually I think of my stories as devoid of sociopolitical commentary. I certainly don't have politics in mind when I write them. They are about individuals interacting with and reacting to primal forces, intelligence abroad in the world. Now that I think of it, these stories deal entirely with questions and situations that bedevil me in real life. So really by extension, it's all about you.