“I’m in over my head” – The Palace

I hope Mr. Tillman is ok.

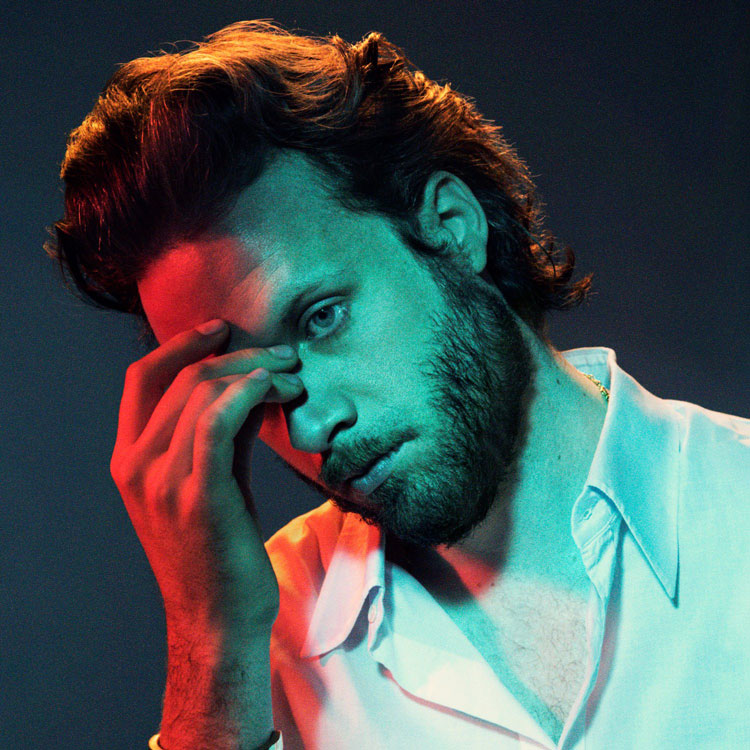

God’s Favorite Customer, the comedown from the brilliant, detached, and cynical Pure Comedy, is an act of deconstruction. Josh Tillman pulls away the mirrors he used to create his Father John Misty persona – an overblown cynic of mythological proportions – and turned them on himself. Dr. Jekyll drowns himself in sorrow to forget what Mr. Hyde did.

Advertised as having no concept, this album is conceptual in its confinement. Written in the aftermath of a two month stay at the Lafayette Hotel, God’s Favorite Customer feels epochal and temporal. From the opening track, there is an immediate sense of place, and headspace. You can see the sun peeking through a hotel blinder onto a disheveled Tillman, bleary-eyed and broken. You can feel the look of existential despair on his face in “Hangout at the Gallows” as he wakes up to his own personal apocalypse, a sea of empty beer bottles, pizza boxes, and his passport in the mini-fridges, ready to start another day of self-pity and loathing.

These images are reinforced on tracks like the pop-diamond, “Mr. Tillman,” the spare “The Palace,” and, from his wife’s perspective “Please Don’t Die.” It’s a heartbreak that the depressed inhabit. When the tracks do not define the physical space, Misty’s headspace, and his imaginings, sorrows, and despair, are front and center, always seeking. Using the scalpel of sharp lyricism a la Harry Nilsson, Randy Newman, and perhaps most prominently, John Lennon, Tillman/Misty examines himself from as many angles as he can justify.

Using the scalpel of sharp lyricism a la Harry Nilsson, Randy Newman, and perhaps most prominently, John Lennon, Tillman/Misty examines himself from as many angles as he can justify.

With that scathing deconstruction, Tillman strips himself bare of his pretenses and strips down the sound to is base components. Featuring a sound palette similar to the early-solo era of Lennon, and Elton John, there is a wonderful balance of low-key tracks, high distortion aperitifs, longing, regretful dirges, and piano ballads, all strung along on a simple straight, hook-y thruline. The bass pops, the drums expand, the synth’s meander, the guitars barrel forwards, and lush production emphasizes the high drama of the mundane feeling of failure.

At the center of it all Tillman is broken and beaten down. Skirting suicidal ideation, depression, and hitting that all-hope-is-lost moment, he sings without seeking resolution. He sings to sing. The catchiness of the hooks, the clarity of his croon, and his self-effacing jibes seek only to release, not to answer. The questions are always more important than the. He sees himself through the eyes of his wife Emma, musician Jason Isbell, and beleaguered hotel concierges, and finds no absolution, only the fact that, at the end of the day, people are only people.

This record does not ascend the labyrinthine heights of Pure Comedy, nor does it have the scathing earnestness of I Love You, Honeybear. Rather, it comes somewhere in the untethered moment when life has exploded like a Michael Bay film, and you find yourself holding the trigger to the bomb; and I love it.

Of all the poet-laureate cynics in the singer-songwriter genre, I have always resonated most profoundly with Josh Tillman. I see myself in his pathological self-awareness. I see myself in his verbosity and need to protect himself with meta-humor and cynicism. I see myself in his earnest devotion to romance, despite his detachment, and in our mutual upbringing in Rockville, Maryland. So, when a record this intimate, damning, and inconclusive is released, I’m satisfied, and trying to cover myself up, questioning whether a damaged love story is more valuable than a spotless diamond.

Until I hang out at the gallows

7,854 out of 10,000