If the depth of a relationship can be measured by how many cocaine-fueled stories you have together, then Doug Stanhope and Amy “Bingo” Bingaman are a pair until death do them part. To say the couple lives “outside of the box” is putting it mildly. Stanhope once compared them to Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid…right before they jumped off a cliff to get away from their pursuers. Stanhope and Bingo teeter on the edge between lawlessness and suicide, adventure and self-destruction, neither willing nor able to surrender to society’s conventions.

Doug Stanhope is a bitingly smart and nauseatingly dark comedian, whose antics are even more outlandish than his stand-up. His brand of gregarious cynicism has won him devoted fans, but he’s no pop comedian. Rather, nearly every description of him contains the words “comic’s comic.” Stanhope himself has conceded the point, “I’m only famous within 100 feet of my show on the night I do the show.”

Bingo, his blue-haired, bipolar, schizoaffective girlfriend, has enough personality for a dozen people. Her wardrobe consists entirely of Tim Burton-esque costumes that pair perfectly with Stanhope’s wild-patterned, retro suits and mismatching ties.

It’s easy to see how they’ve spent the better part of 10 years together, and hard to see how either of them could last that long with anyone else. Stanhope’s fans deeply lamented the couple’s short-lived break up, announced on Stanhope’s podcast after he drunkenly screwed a stripper on a cruise ship while Bingo was still in their room.

As it turns out, their relationship was semi-open, and Bingo was already planning on leaving him anyway for a desert hillbilly named “Washtub Willie.” After a few months of living off-the-grid with Willie, pooping in outhouses and hoarding wild owls, Bingo returned to Stanhope, announcing that they were a package deal, and she couldn’t survive without him.

The home life of Doug and Bingo is surprisingly quaint, if not a little eccentric. While most big comedians station themselves in New York or Los Angeles, Stanhope doesn’t seem to be much for full-time city life. He can’t tolerate the proliferation of “industry tools” and ladder climbing in Los Angeles, so his nomadic tendencies led him to the small border town of Bisbee, Arizona. Bisbee, a former mining town turned artists’ commune, is the kind of place where everyone (all 5,500) knows your name, and the only sports bar in town is Stanhope’s “fun house”.

The couple lives on a compound of fantastically painted homes, caravans, and tin palm trees, and the walls are lined with paintings of Bingo done by artist Gretchen Baer, who considers Bingo her muse. A rotating guest list of slackers, comedic losers, and the local mayor come by regularly to watch football in the “fun house,” join in on Stanhope’s podcast, steep in Bingoness, and drink gallons of vodka sodas. The compound also contains a “suicide house,” where their former roommate Derrick shot himself after his girlfriend died of the sequela of Lupus. Charlotte, Derrick's mother, found the body, followed closely by Bingo. She calls the event a beautiful but tragic love story, and wears the piece of wall with the gunshot on it on a necklace.

During the break up episode of Stanhope’s podcast, it becomes clear that the event had a profound impact on her mental health. She opens up about her current state, confessing to having serious doubts about the nature of her reality and, in a dark turn, telling the crew that she will need to kill herself eventually. By the end of the episode, both fans and Stanhope were left to wonder if Bingo would even be around for the next episode. Luckily, upon returning to Stanhope, the two made subsequent appearances in which she admits being highly medicated, but doing much better. She told the Guardian when asked what it’s like to date Stanhope and have him broadcast her personal business, “I had to own up to who I am, it’s out there. It’s useful now because I can talk about it, it’s not a big deal.”

When she fell into coma after cracking her head during a cocaine-fueled seizure before her 40th birthday party last November, Stanhope didn’t hold back the jokes, tweeting out that Bingo “fell down went boom.” In his longer explanation on his podcast, he added, “All I could think is that’s how she used to fake orgasms.” Later, he tweeted, “BTW, Inappropriate jokes as welcome as hopes, prayers, wishes.”

“I’m only famous within 100 feet of my show on the night I do the show.”

After about a month of hospitalization, Stanhope posted, “Bingo on the mend” on his website, letting everyone know that she was fully conscious, making good progress, and would be coming home to recover. Ever since the Bingo coma 2016, she’s been largely staying private, as any over-stimulation would be bad. In early March, she finally spoke to fans directly, posting “I’m alive!” on Facebook and that she’s fully healed and thankful for everyone’s help and support.

Stanhope was criticized for his seemingly heartless response to Bingo’s coma, but comedy is clearly how he deals with everything. If anything, the more deeply affected he is, the harder he clings to his sense of humor. Making light of an event can serve to belittle it, but it can also comfort, when facing it head on is unbearable. The same goes for Stanhope’s own mother, who committed suicide at 63…with his help.

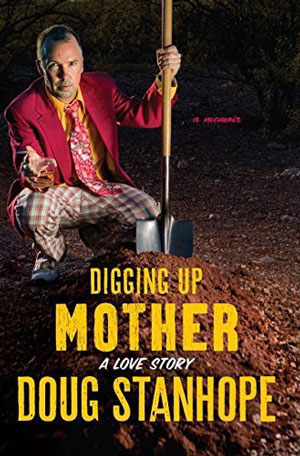

We learn all about Bonnie, Stanhope’s chain-smoking, pill-popping, job-hopping mother in Stanhope’s memoir Digging Up Mother: A Love Story. According to his descriptions, Bonnie was an occasionally suicidal woman who’s done everything from truck driving to bartending to reviewing porn, a kind of deadbeat Renaissance woman, or as Standhope lovingly describes her, “evil yet all heart.”

It’s very obvious that his sense of humor comes from his mother. As soon as he could read, she was leaving Hustler magazines around the house and taking him to see Richard Pryor, not to mention AA meetings, where he’d listen to former drunks recount crazy stories from their past lives. By the time he was in grade school, Stanhope’s sense of humor was so dark that he was repeatedly placed in counseling and sent home.

Bonnie had apparently talked about ending her life with some regularity, particularly after being diagnosed with terminal emphysema. In his book, Stanhope describes how he assumes his mother must feel with the disease as “drowning in your own fluids, like being endlessly waterboarded.” When his mother finally told him she truly was ready to leave the world, he arranged the necessary prescriptions, took Bonnie to his home, and together, with Bingo, threw her a cocktail party to end all cocktail parties, i.e. white Russians spiked with morphine and a healthy dose of mockery. It was a death party that couldn’t have been more suited for Stanhope and his mother if it had been written as fiction.

Not surprisingly, absurdity and crudity play a big part in Stanhope’s controversial comedy, which makes Daniel Tosh look like Shirley Temple. His jokes are often so aggressively repulsive you have to put your food down to listen to them, like his part on the movie The Aristocrats where he manages to make the most appalling joke known to man even more disgusting and then tells it to a baby. And then there’s his escapades in the AOL days baiting and trolling child molesters.

In spite of it all, he’s no shock jock. However inappropriate, his jokes serve a purpose, and it’s not publicity. The twisted vulgarity and violence are rarely the point of the joke, but rather a means to get there. In No Place like Home, he talks about the difference between a “mentally disturbed” person, (i.e. someone with schizophrenia), and a “mentally challenged” person, (i.e. someone with Down syndrome). Throughout the bit, he very tastelessly imitates both. Now, a comedian on stage using the word “retard” and flailing around in an over-the-top imitation is unquestionably offensive. But as the joke goes on, the audience is made to question why they feel so much more discomfort at one imitation and not the other. In the end, he makes the point that although society is generally empathetic, caring, and accommodating when it comes to the mentally challenged, it’s incredibly unfeeling, apathetic, and even hateful when it comes to the mentally ill.

Stanhope also lives out the absurdity of his jokes. He ran for president in 2008, just because, but he dropped out after a month because there was too much paperwork. His biggest show of charity was raising over $100,000 for a woman in Oklahoma who lost her home to the 2013 tornado, not because he felt bad for her, but because she told a CNN reporter, who asked her if she thanked God for her survival, that she was an atheist. “Saying ‘I’m an atheist’ in Oklahoma is like screaming jihad at airport security,” he explained in a video he released after the donation. Stanhope once performed in a maximum security prison in Iceland, coining the term “the Stanhope defense” because the only way his fans could see the show was by committing a crime.

In a bit called "60 Inches of AIDS on Any Given Sunday," he starts a joke by complaining about breast cancer awareness taking over the NFL and ruining his Sunday football. It takes a homoerotic turn as he talks about watching the cameras pan across the players’ thighs in their skin-tight pants, and builds into a five minute, extremely graphic football fantasy in which he rapes one of them. In a twisted, juvenile manner, the joke manages to touch on the corporatization of charity, hyper-masculinity, and the latent homosexuality and homophobia duality in football.

All of Stanhope’s comedy, whether in the form of fantastical stories about football fantasies or jokes about his own, personal, real-life tragedies, seems to function in the same way: if we could all just talk, and joke, about the things that feel so heavy and unmentionable, they wouldn’t be such a big deal. Maybe then we could actually own up to our problems as a society and confront the things we fear in our personal lives. When Butch and Sundance stopped trying to fight the forces of convention and decided to jump off that cliff, they were finally free.

Special thanks to Gretchen Baer for the photos of Bingo and the Stanhope compound. Gretchen is an artist and activist, and is well known for her colorful oil paintings, crazy art cars, and flamboyantly- themed musical, art and political events. Please visit her site for more photos and original art.