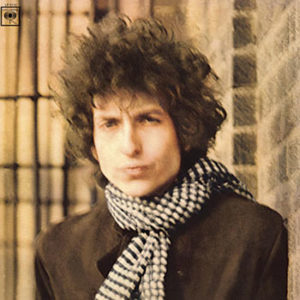

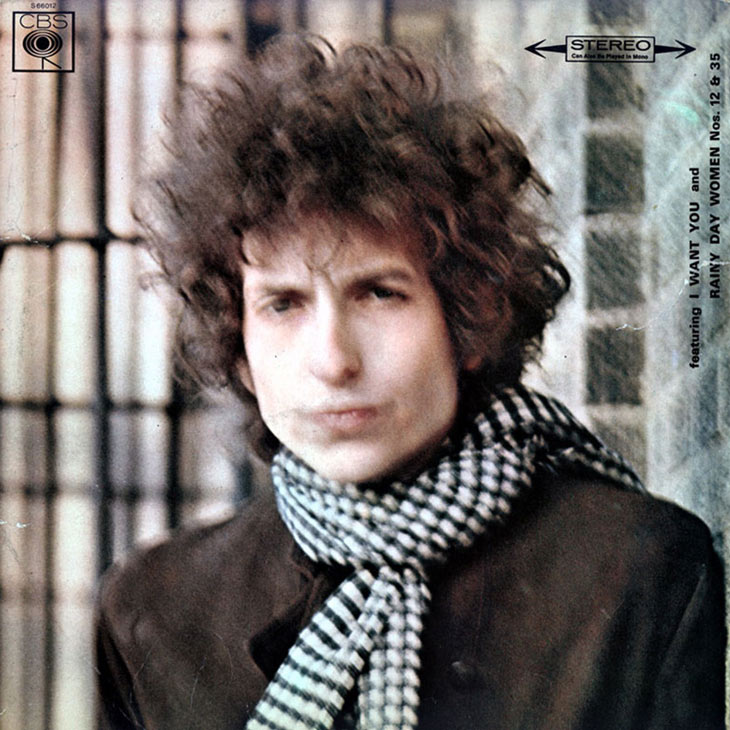

Bob Dylan Blond on Blonde

Bob Dylan-Blonde on Blonde

My voice scares me. It’s among the reasons I despise this album—and Bob Dylan, more generally. In fact, Blonde on Blonde is the first album on this list which I legitimately despise. I can’t deny its lyrics are poetic and poignant, and the marriage of folk-rock music with modernist lyrics is compellingly Dantean in its marriage of high and low art forms. Honestly, there are some genuinely beautiful moments, such as “Visions of Johanna,” and the 11-minute finale “Sad Lady of the Low Lands.” But that doesn’t make me despise it less.

Some of my complaints are purely musical. Like The Rolling Stones’ Exile on Main Street, and the Clash’s London Calling, I don’t think this album needs to be 77 minutes for a series of musically (if not lyrically) straightforward folk-rock songs, with some electric flourishes. Additionally, I’m in the party of those against Dylan’s singing style, more particularly the affectation that is so clearly affectation that it sounds sarcastic.

But my over-the-top hatred for this record is not due to the music; my hatred has two primary parents: myself and acclaim.

Greatness has a point of diminishing returns. Ask someone who has been told that Citizen Kane (1941) is the greatest movie of all time, and watch the disappointment grow, when they cannot, for the life of them, figure out how that could be. It’s just about an old rich guy and his regrets. Qualities such as the heavy use of deep focus, or the revolutionary use of make-up, aren’t immediately evident, especially as time goes on. So it is with Blonde on Blonde and Bob Dylan. I’ve heard from so many people that Dylan is the greatest, most influential, most (insert superlative) musician ever, and it drives me crazy. The fact that he has been so elevated makes me less inclined to enjoy his music.

Greatness has a point of diminishing returns.

And I should note, I do understand the appeal. Marrying modernism to blues is no small task. Doing it seamlessly, where the Allen Ginsberg- and James Joyce-like lyrics mesh so tightly with the blues and rock style, is incredibly hard to pull off. I commend Dylan for it, particularly on this album and the upcoming Highway 61 Revisited.

If you’ve ever listened to a recording of yourself, and noted how awful you sound, it’s not because your voice is bad, but because your voice has been stripped of its motivation. I am, by no stretch of the imagination, a genius. I am intelligent. But I can be pretentious, a know-it-all, and I enjoy five-dollar words. Hearing Dylan, and his lyrics, I often encounter all those things I hold meaningful, as other people see them, and it scares me. On his most famous records, I see them most obviously, which makes listening to this record in particular, a double record, particularly galling – musical boredom aside. Hating my own voice matters in understanding my hatred of this record. It drives me kind of insane. So the affectation becomes torturous, and the lyrics pretentious; and so I despise it.

And that’s the problem of greatness.

Until I’m wearing a leopard skin pill box hat.